Pottery

Traditional Cretan Pottery

Preparation Of Cretan Clays

Crete is the richest area in quantity and quality of clay in the whole of Greece. Experienced potters recognise the various clays and their properties by eye and feel. The following clays are used for making pots:

· Kokkinohoma , a fine-grained red clay used for making strong vessels with thin walls and a smooth surface without further processing.

· Lepida , a hard, compact clay very common in Crete. This is mainly used as the top layer of mud roofs, as it is waterproof. It is usually grey-blue and, more rarely, dark red in colour.

· Koumoulia , a fine-grained, light yellow clay which gives vessels a smooth surface.

Clays vary greatly depending on the quality and quantity of other natural substances they contain. Their properties vary accordingly and are of course transferred to the end product.

Cretan traditional potters, drawing on millennia of experience, exclusively use the three types of clay mentioned above, on their own or in admixtures :

The percentage of each varies depending on the natural qualities of the clays, with a mixture of 60-80% lepida and 20-40% kokkinohoma used to make pithoi.

Clay Extraction And Processing

Once the clay has been extracted with a pickaxe and transported to the workshop, it is pounded with a wooden pestle. Wood, a relatively soft material, is used so as not to break the small stones which may be in the clay. The pounding turns the lumps of clay into powered earth.

The next stage is sifting the earth, using first a large sieve and then a much finer one for clay intended for small pots. In the latter case, the end product will be placed in a tank, with 1 part clay to 3 parts water. The heavier elements in the clay (stones, metals etc.) will sink, while the pure clay remains suspended on the surface of the mud. This process is known as levigation .

Once the water has evaporated, the homatas removes the suspension with a spade and places it in a second tank, where it will be dried out further. Once the clay is compact enough, it is cut into large pieces for the potter to knead (wedging) and throw on the wheel.

In the case of pounded lepida, the powdered clay is not levigated in tanks but mixed with kokkinohoma clay, with the addition of a little water, and pressed with the feet, like grapes in a wine-press. This clay is suitable for large pots such as pithoi.

Cretan Potters’ Wheels

The classic wheel for making small pots (the kickwheel) is found across Europe. It is comprised of a small round, revolving work surface (the head) connected by a vertical shaft to a much larger wheel which the potter works with his left foot, sitting to the right of the wheel. The entire mechanism is made of wood and set in a special area of the workshop. A potter’s workshop was discovered by chance in a Minoan villa, with the same layout but a round wheel head made of clay, which may have been set on a wooden base. However, it is an important indication that the Cretan potter’s wheel has remained unchanged since the 16th century BC.

The trohi is a low hand wheel with a large round head, used exclusively for making pithoi. Trohia are always used outdoors in rows for technical reasons.

The body of the pithos is build up of a series of clay strips. Before the next strip can be added, the previous one must have dried enough and hardened to a certain degree, but still be sticky enough for the fresh clay to be attached. For this reason the potter works on a series of 6-7 trohies in row, so that by the time he comes back to the first the clay will be dry and hard enough to attach the next strip.

Kilns

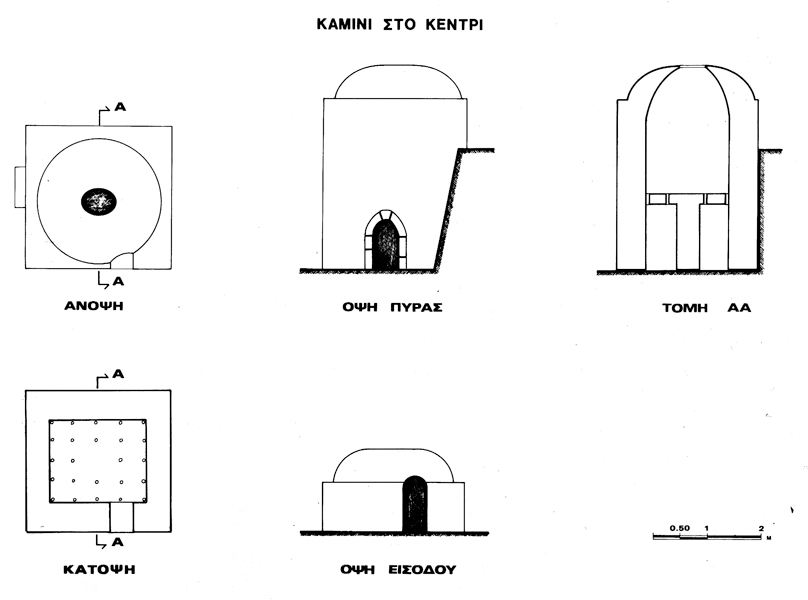

There are two types of kiln in Crete, the open and the closed kiln.

Open kilns

The commonest are the open kilns found in the potters’ centres Kendri, Thrapsano and Margarites, and the rural kilns found across Crete. These are in the shape of a cylinder in various sizes, partly sunk into the ground. In the middle of this built cylinder is a thick grille, the firing platform, perforated with many holes which allow the heat in the combustion chamber to reach the area containing the pots. The firing platform is set on a pedestal placed in the centre of the combustion chamber. The upper chamber of the kiln, which is stacked with pots, is open and has a fairly large door for placing and removing large vessels.

Before the fire is lit, the door is blocked up with large stones and clay while the roof is roughly covered with large potsherds, which are laid touching the sides of the kiln and the pots below.

Closed Kilns

Closed kilns are found only at Nohia. They are rectangular and capped with a dome with an elliptical vent, which the kaminiaris covers or uncovers depending on the progress of firing.

The operation of the kiln, in which the pots are cooked by a high-temperature fire, is a particularly delicate and complex affair, for which the kaminiaris was responsible in the days before measuring instruments such as thermometers, pyrometric cones or clocks came into use. In general terms, at the start of the process the fire should be very low for about two to three hours, in order to dry out the pots completely without cracking them. The fire is then built up gradually for seven hours and left at a high temperature for a further three. Firing in a large kiln lasts about 12-14 hours. The temperature in traditional kilns used for firing large vessels must not exceed 900οC or the pots will gradually melt and disintegrate.

A large log is then added to the combustion chamber so that the temperature inside the kiln is gradually lowered, thereby avoiding cracking or breaking.

The pots in the kiln may not be removed until at least 12 to 18 hours later, depending on the outside temperature.